Blue Like Jazz, a philosophical and spiritual self-examination by Donald Miller opens with, “I never liked jazz music because it doesn’t resolve.” The author shares a memory of observing a man playing the saxophone outside a theater. The musician didn’t open his eyes for fifteen minutes.

“After that [Miller says] I liked jazz music. Sometimes you have to watch somebody love something before you can love it yourself. It is as if they are showing you the way. I used to not like God because God didn’t resolve. But that was before any of this happened.”

The best thing that came out of earning my doctorate a few years ago was being forced to truly examine my beliefs (which is also the scariest thing I’ve ever done). I used to be afraid to question things too deeply. I was afraid things wouldn’t resolve. But that was before any of this happened….

I began that journey looking through the lenses of some pretty thick glasses. I really never paid much attention to them sitting right there on my nose coloring my perspective on everything. I grew up with them. They felt natural. For all of us, the world comes into focus through lenses that have been adjusted to fit our own personal DNA, culture, and experiences.

“Men and women are not only themselves; they are also the region in which they were born, the city apartment or farm in which they learned to walk, the games they played as children, the old wives’ tales they overheard, the food they ate, the schools they attended, the poems they read, and the God they believed in.” (from Maughm, The Razor’s Edge)

Although none of our lenses could ever be identical, for the most part, I interacted with people whose vision was very close to my own. We wore the same rural, southern, white, American, Christian prescription. So, there never was much need to notice them or explain them to others or even myself.

Every once in a while, I had to wrinkle my nose and squint through my glasses when I bumped into someone whose view of the world was different than my own. I am a special education teacher because of one such collision with a little boy considered severely and profoundly disabled. He was non-ambulatory, non-verbal, and non-compliant. I became a first-hand witness to how a simple communication device eased his frustrations and gave him a way to begin expressing all that was trapped in his beautiful mind. Because of him, physical appearance no longer limits my perception of a person. Although, on occasion, I allowed certain people, ideas, and experiences to adjust my prescription ever so slightly; for the most part, I remained blissfully unaware I was seeing through glasses in the first place. Until, they were called starkly to my attention. At first, it was unsettling to even reach up and feel for them and frightening to think about taking them off. I was afraid of losing my balance, but looking back I learned as Gail Sheehy once said, “growth demands a temporary surrender of security.”

I remember an assignment early on to write a blog about our “emerging research identity.” I used the metaphor of a chrysalis. A cohort member posted the following comment. I’ve thought about it often.

“There is a point in metamorphosis where the entity inside is neither caterpillar nor butterfly, but simple “mush”—pure potential. M.C. Richards referred to a similar idea. She talked about the ‘crossing point,’ such as in a plant, where a fine membrane (one cell thick) of intelligence separates the growth of a shoot upward toward the sun, and the growth of roots into the earth. This is a great, creative place to be.” – Susan Reed

I chose this metaphor without realizing how truly fitting it would become. Many sleepless nights, the word “mush” summed it up quite well—an exciting, wonderful, pressure-filled, uncomfortable place to be. Searching for resolve. Pure potential. (Collectively, maybe this is where we all are now: pressure-filled, uncomfortable—but, pure potential.)

As I examined my convictions alongside those of others and took a hard look at my personal lenses rather than through them, I emerged from my chrysalis not any less of myself, but more. A much broader perspective developed, along with new ways to get around and make sense of the world. I still mattered, but only as part of a much bigger, grander picture.

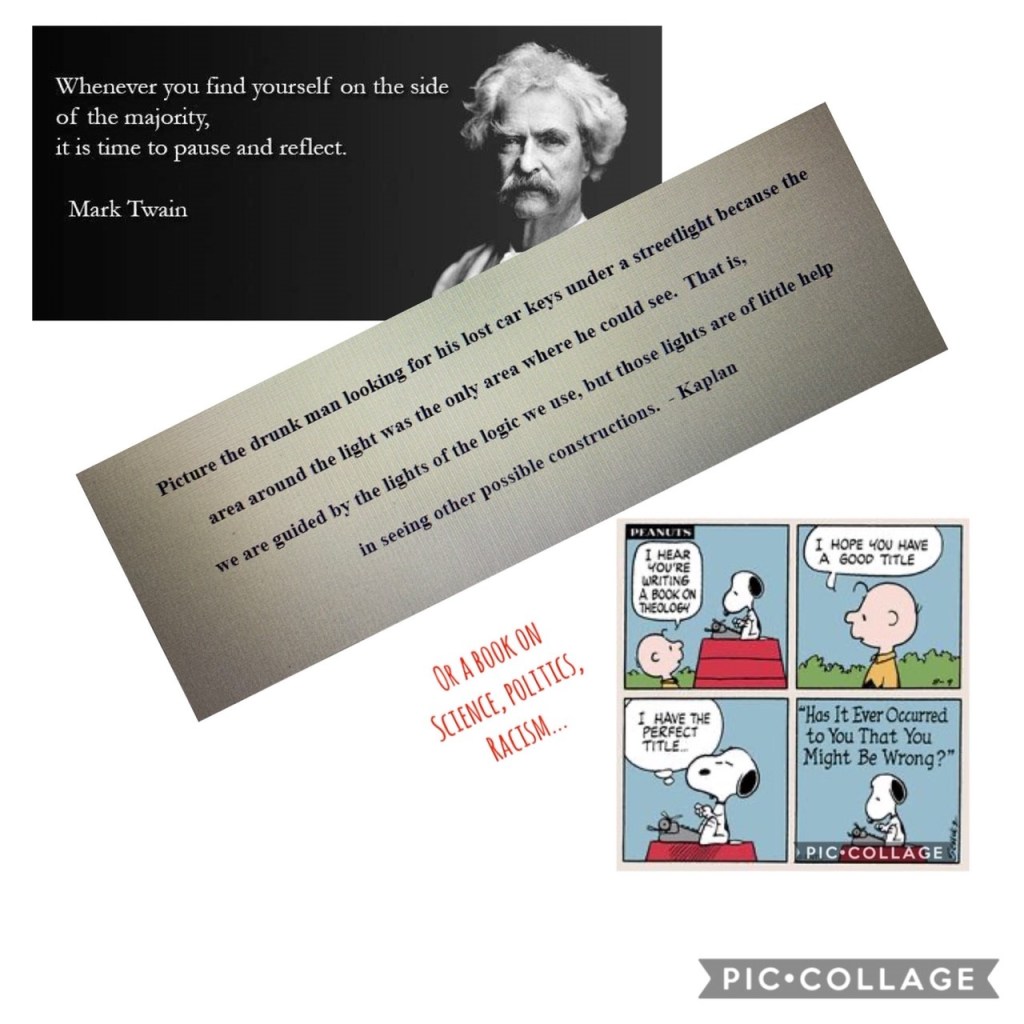

I remember feeling like I was in the story of the six blind men arguing over unwavering descriptions of the elephant. Based on direct observation, they each walk away with a different conclusion equally convinced of their knowledge. One man examines the trunk and professes the animal is snake-like. Another finds the tusk and argues that the animal is most like a spear. A third kneeling on his knees gropes a thick leg and envisions the trunk of a tree. The tail is compared to a rope and the ear, a fan. After falling into the elephant’s side, the last man insists the beast is most like a sturdy wall. Although each man was partly right, they all were ultimately in the wrong. Perhaps Mark Twain said it best, “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

So, I reached for my glasses. I didn’t let go of them; they were part of me, but I pushed them back on top of my head and let fuzzy images of new perspectives come into focus. I began to question. Although I was realizing how presumptuous it is for any of us to believe we were lucky enough to be born in exactly the right little corner of the world where we got it all exactly right the first time, I could not just let go of the elephant. There had to be one. Parts of it had been discovered. I had touched it myself.

Despite a lifetime conditioning me to be content as a recipient of knowledge, I slowly became a questioner. I found out, not only was the ground still under my feet, there was also stability over my head and all around me. Outside the lines and boxes I had drawn for myself, my new view of reality was more dazzling, chaotic, precise, multi-dimensional, and absolute than I could have ever imagined.

The lines and boxes we’ve all drawn for ourselves seem to have backed us all into tight corners. Recently, however, it seems more and more lines are being crossed. It only takes turning on the news, reading posts on any social media website, or even tuning in to Sunday morning sermons to observe one another in a defensive stance. At the same time, never has there been such economic, political, and cultural interdependence. It is becoming increasingly difficult for opposing points of view not to collide. There is a sense of urgency. People representing every possible perspective are desperately seeking a way to maintain control. At such a pivotal point in our society, Margaret Wheatley offers a profound proposition, “What if we could reframe the search? What if we stopped looking for control and began, in earnest, the search for order? Order we find in places we never thought to look before…. Is it possible that our conditioned narrowed focus is blinding us to what is significant? “ Although it is frightening to suspend a worldview, it is conceivable that we can at least begin to adjust our glasses. Even reaching up to notice we are wearing them in the first place could have far reaching effects. No matter our personal beliefs and experiences, humanity is our common denominator. Whether we like it or not, we are part of one another.

My personal journey toward resolve could never have happened if I refused to acknowledge my glasses. I did not get rid of them. It is because of them, I possess a perspective that enables me to offer a unique contribution to something much bigger than myself. Acknowledging them, however, allowed me to see that there was something much bigger than myself in the first place. Zohar & Marshall describe society as a “repository of skills, knowledge, and potential… not possessed by any one of its members.” The authors reference the idea that a whole is not identical to the sum of its parts. It is something new. In order to draw from this abundant source of supply, we must learn to appreciate our underlying unity expressed as diversity. We must make an effort to get to know people different from ourselves.

“People who are different from us – whose differences we acknowledge and understand – help us realize that we aren’t the center of the universe and that other people’s experiences are equally valid. This ability to see the world through someone else’s lens greatly expands our ability to navigate in an increasingly complex world and to do so with skill and grace.” – Mara Sapon-Shevin

Think about it this way. It is necessary for musical compositions that each of the eighty-eight keys on a piano keyboard produces a different sound. In this writing alone, 26 uniquely individual letters of the alphabet make up over 1,829 words. The same is true with people. Our whole is not identical to the sum of our parts. It is something new.

Imagine if we all at once could just push our glasses back on top of our heads and blink? And bravely, let fuzzy images of new perspectives come into focus. We shouldn’t get rid of our glasses. It is because of them that we possess individual perspectives that enable us to offer unique contributions to something much bigger than ourselves. Acknowledging them, however, allows us to see that there is something much bigger than ourselves in the first place.